On the evening of September 28, 2011 hundreds of Kentuckians gathered in downtown Louisville to catch a glimpse of a distinguished group of men who were visiting the state. The classic red carpet treatment one would expect for such an event was rolled out over a section of Main Street while a gigantic American flag waved overhead.

Those honored to walk this red carpet however were not movie stars or musicians. They were members of the most elite group in America, who earned their fame through blood, sweat and tears. During some point in their lives they had been either shot at, blown up, burned, broken, beaten, starved, imprisoned and in some cases, all of the above. For their heroism they earned our nation’s highest military award for valor, the Medal of Honor (MOH).

History of the Medal

Originally created in 1861 by Abraham Lincoln, the Medal is bestowed upon members of the Armed Services who distinguish themselves in battle by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of their life above and beyond the call of duty, while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States. In 1958 President Dwight Eisenhower signed a piece of legislation forming what is known today as the Congressional Medal of Honor Society (CMOHS). Since its inception there have been 3458 recipients. There are only 85 living recipients today.

Every year, the Medal of Honor Society holds a convention in a host city for those distinguished service members who have received this prestigious award. The city of Louisville, Kentucky was delighted to have the 2011 convention because this year marks the 150th Anniversary of the medal’s creation and more importantly the most recent recipient of the award, Cpl. Dakota Meyer, hails from nearby Greensburg, Kentucky. Besides being the youngest, he is the first living Marine since the Vietnam War to receive the honor. Although he is a mature and serious 23-year-old man now, he was only 21 when he defied death numerous times to save the lives of his friends.

Most of the events were held in Louisville’s Galt House Hotel which sits right of the riverfront.

Part of the 2011 convention of the Medal of Honor Society

was held at Churchill Downs, Louisville, Kentucky.

Convention Events

Besides the opening day red carpet treatment dubbed the Walk of Heroes, there were a number of other events which provided locals the chance to meet and honor members of this distinct group. One of the conventions premier events was the Tribute to American Valor held at the Yum Convention Center.

The evening began with a demonstration by the famous Marine Corps Silent Drill Team followed by theatrical narrations of select recipients from wars going all the way back to World War II. When the skit was finished the actual person who performed the deeds would step onto the stadium floor to thunderous applause.

Considering the location of this year’s event, it is not surprising that organizers chose to single out those from the Bluegrass State. Kentucky has had 56 honorees accredited to the state. Don Jenkins, from Quality, Kentucky was working in the coal mines when at 19 he was drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam in January of 1969.

During an intense fire fight he ran into an exposed area cradling an M-60 machine gun. When it ran out of ammo, he grabbed a rifle, and then made multiple trips through heavy fire to get more ammunition from dead GIs. He later grabbed two anti-tank weapons and ran straight at the enemy once more, taking out two enemy bunkers. After receiving shrapnel wounds in his legs and stomach, Mr. Jenkins heard the cries of help from fellow soldiers trapped in the midst of the battle. He ignored his injuries and went back into the fray on four more occasions and dragged those men to safety. He returned to the U.S. later in the same year, received his medal in 1971 and returned to the coal mines of Kentucky until he was forced to retire in 1999 because of disability.

Sgt. Gary Litrell, a former president of the CMOHS is from Henderson, Kentucky. He earned his medal in Vietnam in 1970 during a four-day battle where he showed superhuman endurance. His was an advisor to 473 fellow Vietnamese Army Rangers who were attacked and almost overwhelmed by 5000 enemy troops. When his commanding officers were killed Sgt. Litrell took command and over the next four days he repeatedly abandoned a position of relative safety to direct artillery and air support, distribute ammunition and help the wounded.

The best was saved for last when the deeds of Dakota Meyer were recounted. Cpl. Meyer received his medal for saving the lives of 36 American and Afghan soldiers and Marines who were ambushed by a much superior Taliban force in the village of Ganjgal. During a battle which lasted over six hours, Cpl. Meyer made five trips into the fire fight with the certainty he would not come out alive. On a several occasions, he was forced to fire, at point-blank range upon enemy soldiers trying to take over his vehicle.

Cpl. Myer merely stood there with hands folded in silence as the audience applauded the narration of his feats. Like all MOH recipients he feels he did nothing worthy of praise. “I was only doing my job,” he often responds to those who laud his actions.

Visits to Schools

The recipients also took time to participate in an outreach program in which some of them visited fifteen area schools throughout the Jefferson Country public school system. They were received with admiration by star struck youth, who sat up straight, and hung on their every word.

Louisville did something different from other host cities in the past. Each of the recipients received a personalized welcome letter from an area high school student. The envelope carrying the letter described how the class had “read about the Medal of Honor recipients who were coming to the convention and wanted to be sure you knew how much it means to them that you are here.”

Col. Harvey Barnum received a letter from a student at East High School who explained he was contemplating the military life because of the example of men like him. The student then briefly narrated Col. Barnum’s deeds and how he was able to “rally his troops” and “raise the moral of the other units while under heavy fire.”

“This to me is amazing,” he said, “and something I don’t believe I could do. You give me an inspiration and make me want to give back to this country.”

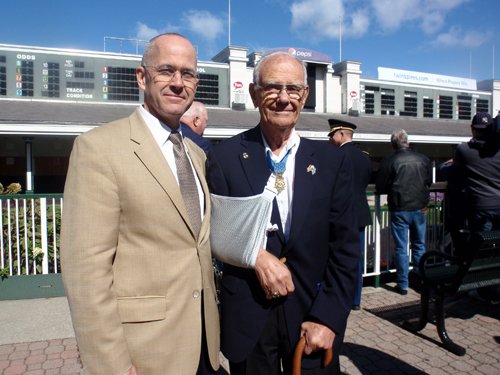

Mr. Norman Fulkerson with Col. Walter Marm,

recipient of the Medal of Honor.

“It’s Like They Have a Halo Around Them”

A visit to Louisville would not be complete without a trip to historic Churchill Downs. After taking a look at 2003 Kentucky Derby winner Funny Cide, in the paddock area — brought in especially for the occasion — the heroes were treated to lunch in Churchill Downs 4th floor Millionaire’s Row. Since it was open seating, attendees could pick the hero of their choice to have lunch with. I was honored to sit at the table of Col. Walter Marm. To my left was Cory Etchberger, the son of MOH recipient Richard Etchberger. His father was killed during heroic actions in Vietnam but was only awarded the Medal last year.

He shared his thoughts on the experience of attending his first convention and one particularly interesting story about a lady he bumped into named Michelle. She was in town for a Christian Education convention and at the suggestion of her husband decided to stay on for a couple of days. To her surprise she ran into Cory who explained the convention and the feats of some the men standing around her. She was amazed at her good fortune but overwhelmed when Mr. Etchberger kindly offered to take her picture with MOH recipient Col. James Fleming. She was speechless as she walked away in tears.

I had a similar experience when I spotted Don and Sherry Gilbertson in the Churchill Downs museum. They are from Pebble Beach, Fl. and just happened to be in town for a car show. Mrs. Gilbertson could hardly contain her enthusiasm for the opportunity to just stand in the same room with such heroes. “I feel in awe just being next to them,” she said. “It’s like they have a halo around them.”

When the recipients gathered for a group photo in the paddock area, a lady standing next to me could hardly contain her childlike enthusiasm as she took one picture after another. “Oh, my gosh,” she just kept exclaiming, “oh my gosh!”

On the way out I happened to jump on the elevator with a Churchill Downs employee who felt the need to share his experience of the day. He described watching each of the recipients as they walked across the blue carpet and into the park. “I could hardly keep my eyes dry,” he said.

The distinguished group of Medal of Honor recipients attending this years event. During some point in their lives they had been either shot at, blown up, burned, broken, beaten, starved, imprisoned and in some cases, all of the above. For their heroism they earned our nation’s highest military award for valor, the Medal of Honor (MOH).

Informal Conversations

It is hard to describe what it was like being in the midst of such men. It seemed like everywhere you turned you were either in the presence of a hero or someone related. At Churchill Downs, I happened to be standing next to Megan, the 23-year-old daughter of Army Specialist John Baca. He could not make it to the event but she described how her father jumped on a live grenade during the Vietnam War and lived to tell about it. This act of selflessness is not an uncommon thing among American servicemen.

Standing next to her was the daughter of Sgt. Maj. Allan Kellogg. I had met him the day before and was impressed with the way he calmly told of his encounter with a live ordnance during his 1970 tour in Vietnam.

The grenade bounced off his chest and landed at his feet as he was leading his men through a rice paddy. Sgt. Kellogg jammed it into the mud then fell on it. The subsequent explosion knocked his .45 pistol out of his hands and detonated his ammunition belt. In spite of the severity of his injuries, he reassumed command of his men and led them to safety.

Col. Don Ballard, a hospital corpsman in Vietnam, was also at the convention. On May 16, 1968 his company was ambushed by a North Vietnamese unit. He was caring for a Marine who had been badly wounded when another Marine yelled “grenade.” Col. Ballard refused to allow any harm to his patient and instinctively jumped on it. After what seemed like an eternity — and no explosion — he stood up and threw the grenade which detonated in midair.

Mr. Norman Fulkerson (left) with Medal of Honor recipient Mr. Robert Maxwell.

World War II veteran Robert Maxwell was not so lucky. He and I chatted in front of Churchill Downs paddock area where he told about the feats which earned him our nation’s highest honor.

He was holding some Germans at bay during a firefight with only his .45 pistol. Suddenly a grenade landed in the courtyard of their compound only a few feet away from the door of the command post. His first impulse was to throw it but feared there would be no time to do so. He then decided to smother it with his body so as to save others from injury. What most impressed me about him was his “grandfatherly” kindness and willingness to recount a story he has told so many times before.

These informal conversations were, by far, what made the convention most special. I found myself constantly gravitating between an objective reporter of events and an adoring fan. I was not alone.

Col. Jim Coy is a retired Medic with the Special Operations who served as the senior surgeon with the Army Special Forces. In spite of his own noble service to our country he, like many other hero worshipers, patiently waited as the recipients passed to get their signatures in a beautiful book titled, Medal of Honor; Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty by Nick Del Calzo and Peter Collier.

Another permanent fixture in the hotel lobby was Dave Loether. His son is currently serving our country in Afghanistan with the U.S. Army. Among Mr. Loether’s most prized possessions is a flag he proudly unfurled for me. He had it signed by all the Army MOH recipients as a gift for his son.

“The Biggest Honor I Have Ever Had.”

The convention’s final event was the Patriots Awards Dinner. Officer Patterson stopped me at the entrance to check my identification. He was involved in escorting the recipients and explained how impressed he was at the reception they received from the public. “As each of them arrived in the airport,” he said, “they were welcomed with a standing ovation from passengers. People would approach to touch them and shake their hand.”

During the cocktail hour, a charming Kentuckian named Tonnia was serving hors d’oeuvres with a big smile on her face. “What do you think about this group of men?” I asked. “I feel special just being here,” she responded.

Clay Smith expressed similar sentiments. He was one of the bus drivers hired to transport the recipients during the week’s events. I had seen him earlier in the day holding the door to the entrance of Churchill Downs with one hand, while playing “My Old Kentucky Home,” on a harmonica, with the other. Being a die-hard Kentuckian, I gave him thumbs up for his performance.

He explained how the harmonica was a gift given to him by Sgt. Sammy Davis. When he opened the box I could see it was engraved with Sgt. Davis’ favorite saying, “You don’t lose until you quit trying.”1

“I cried for over an hour after receiving such a gift,” Mr. Smith said. “I have driven this bus for over 30 years,” he continued, “but this has been the biggest honor I have ever had in my whole life.”

by Norman Fulkerson

No comments:

Post a Comment