by Luiz Sérgio Solimeo

Humility, Magnanimity and Magnificence

True Humility Is Not Contrary to Legitimate Splendor and Honors

The virtue of humility, at least in its external aspects, arouses much sympathy even among those who are not particularly religious or otherwise oppose religion. In a world dominated by pride and sensuality, it seems very timely to study this virtue, however briefly.

An Interior Act of Submission to God

As with any virtue, we must first consider humility in its interior aspect, its essence. There is no better teacher to lead us in this task than the Common Doctor, Saint Thomas Aquinas.

According to him, “humility properly regards the subjection of man to God.”[1] Therefore, it predisposes man to practice all the virtues, which consist in submitting our intellect and will to God.

Saint Thomas Aquinas (Angelicus Doctor), lays down the principle that one virtue cannot contradict another. Humility is perfected and guided by the virtue of prudence, thereby avoiding errors that may cause scandal and confusion.

Being Detached Without Despising the Gifts Received

Humility leads to detachment from self. It moderates our desire for excellence, keeping it in due proportion[2] and leads to a healthy self-abasement. But when this is done to seek one’s own glory, it is false humility, a fruit of pride.[3]

True humility does not prevent us from recognizing the gifts received from God. “It is a sign of humility if a man does not think too much of himself, observing his own faults; but if a man contemns the good things he has received from God, this, far from being a proof of humility, shows him to be ungrateful.”[4]

There Is No Contradiction Among Virtues

Saint Thomas lays down the principle that there can be no contradiction between one virtue and another.[5] Therefore there is no contradiction, for example, between the virtue of humility, on the one hand, and the virtues of magnanimity and magnificence on the other.

Thus, humility and magnanimity complete one another because “a twofold virtue is necessary with regard to the difficult good: one, to temper and restrain the mind, lest it tend to high things immoderately; and this belongs to the virtue of humility: and another to strengthen the mind against despair, and urge it on to the pursuit of great things according to right reason; and this is magnanimity.”[6]

“[M]agnanimity urges the mind to great things in accord with right reason. Hence it is clear that magnanimity is not opposed to humility: indeed they concur in this, that each is according to right reason.”[7]

A Seeming Contradiction

The reason why humility seems to contradict magnanimity is because these virtues consider two different aspects: “magnanimity makes a man deem himself worthy of great things in consideration of the gifts he holds from God: thus if his soul is endowed with great virtue, magnanimity makes him tend to perfect works of virtue; and the same is to be said of the use of any other good, such as science or external fortune. On the other hand, humility makes a man think little of himself in consideration of his own deficiency.”[8]

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at age 14.

True humility does not prevent us from recognizing the gifts received from God. “But if a man contemns the good things he has received from God, this...shows him to be ungrateful.”

To Despise Honors Is to Despise the Ornament of Virtues

“Those are worthy of praise who despise riches in such a way as to do nothing unbecoming in order to obtain them, nor have too great a desire for them. If, however, one were to despise honors so as not to care to do what is worthy of honor, this would be deserving of blame.”[9]

“Magnanimity,” Saint Thomas concludes, “is the ornament of all the virtues.”[10]

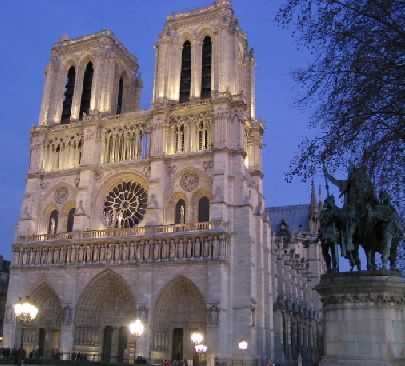

Humility and Splendor

Humility does not clash with the virtue of magnificence, through which we seek splendor, especially in God’s worship. This is because the magnificent does not seek greatness as such but rather for God’s glory.

“The intention of magnificence is the production of a great work. Now works done by men are directed to an end: and no end of human works is so great as the honor of God: wherefore magnificence does a great work especially in reference to the Divine honor. Wherefore the Philosopher [Aristotle] says (Ethic. iv, 2) that ‘the most commendable expenditure is that which is directed to Divine sacrifices’: and this is the chief object of magnificence. For this reason magnificence is connected with holiness, since its chief effect is directed to religion or holiness.”[11]

The magnificent does not seek greatness for itself but rather for God’s glory. The virtues of magnanimity and magnificence drive us to great achievements and incline us to pursue excellence and splendor – for the greater glory of God.

Humility Is Guided by Prudence

For Saint Thomas, humility, like all moral virtues, is perfected and guided by the virtue of prudence, the first of the virtues when it comes to practical action.

Prudence, he says, is “the principal virtue in practical matters.”[12] “Prudence [is] the complement of all the moral virtues…. [T]he knowledge of prudence pertains to all the virtues.”[13] “Prudence is the conductor of the virtues.”[14]

Thus, the practice of humility should be guided by prudence by applying general principles to concrete situations[15] and thus avoiding an erroneous assessment of occasions, circumstances and posts in which a person should practice humility. Prudence therefore avoids, in the practice of humility, errors which may cause scandal and confusion by disparaging one’s own office, especially ecclesiastical, and by showing contempt for the virtues of magnanimity and magnificence, whose practice is required by the office.

Accepting Honors in Submission to God

Honors due to superiors may be owed because of their personal virtue or because of the excellence of their office; for this latter reason, even bad superiors must be honored: “A wicked superior is honored for the excellence, not of his virtue but of his dignity, as being God’s minister, and because the honor paid to him is paid to the whole community over which he presides.”[16]

Since the essence of humility is the inner act of submission to God, the external manifestations of this virtue should be aligned with this submission to the divine will, which has called someone to high office — whether civil or ecclesiastical — by accepting the splendor and honors linked thereto.

Summarizing

Humility is the virtue by which we fully submit ourselves to God and moderate our disproportionate desires of grandeur. Through the virtue of humility we abase ourselves in consideration of our faults and smallness before God.

The virtues of magnanimity and magnificence drive us to great achievements and incline us to pursue excellence and splendor.

Just as we honor those who are superior to us either because of their virtue or their office, so also we should receive the honors destined to us on account of the gifts we have received from the Creator or the office we occupy. We credit these honors to God and to the dignity of the office, rather than to our personal merits.

Since the moral virtues are guided by prudence, we should not perform public acts of abasement inconsistent with our office, as in doing so we would commit an act of imprudence and give occasion for scandal and confusion, shaking the faith of others.

Due to the harmonious unity existing between all the virtues, regardless of the circumstances, we cannot emphasize one virtue against another — at least in people’s eyes.

“Humility Is to Walk in Truth” (Saint Teresa)

It is worth recalling here the words of Saint Teresa of Avila:

“Once I was wondering why Our Lord was so fond of this virtue of humility and the answer immediately occurred to me: It is because God is the supreme Truth, and humility is to walk in truth; so it is well for us to see that all we have is misery and nothingness; and he who does not understand that, walks in a lie.”[17]

Humility expresses the truth about ourselves and about others and counters false humility, which is based on a lie.

1.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 162, a. 1c; cf. ibid. q. 161 a.1, ad 5, and a.2, ad 3.↑

2.

Cf. Ibid., II-II, q. 160 a. 2c.↑

3.

Ibid., II-II q. 161, a.1 ad 2.↑

4.

Ibid., I-II, q.35, a.1 ad 3.↑

5.

Ibid., II-II, q. 129, a3 obj. 4.↑

6.

Ibid., II-II, q. 161, a.1c.↑

7.

Ibid., II-II, q. 161, a.1, ad 3.↑

8.

Ibid., II-II, q. 129, a.3, ad 4.↑

9.

Ibid., II-II, q. 129 a.1 ad 3.↑

10.

Ibid., II-II, q. 129, a4, ad 3.↑

11.

Ibid., II-II, 134 a.2 ad 3.↑

12.

Commentary on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, book VI, no. 1256, translated by C. I. Litzinger, O.P., (Notre Dame, Ind.L Dumb Ox Books, 1993).↑

13.

Summa Theologica, II-II, 166 a.2 ad 1.↑

14.

II Sententiarum, dist. 41, q. 1, a.1 ob. 3.↑

15.

Summa Theologica, II-II q. 47, a.6c.↑

16.

Cf. Ibid., II-II q. 103, a. 2 ad 2.↑

17.

St. Teresa of Avila, Las Moradas, chapter 10, no. 7,

http://hjg.com.ar/teresa_moradas/moradas_6_10.html.↑

No comments:

Post a Comment