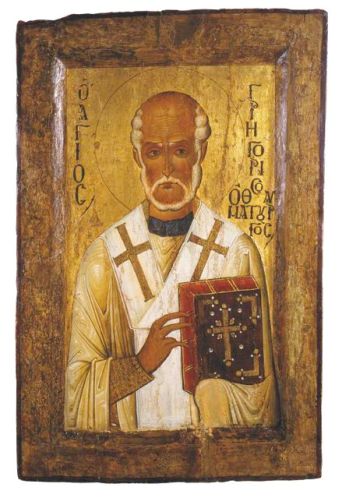

Saint Gregory Thaumaturgus (the Wonderworker)

November 17 is the Feast of Saint Gregory

According to Saint Basil, Saint Gregory Thaumaturgus (the Wonderworker) is comparable to Moses, the prophets and the apostles.

Indeed, his works were many. He moved a huge boulder that was in his way preventing the building of a church. He dried out a pond that was a cause of discord between two brothers. In order to stop the River Lycus from its frequent and damaging floods, Gregory planted his staff at a safe point near the river bank. He then prayed that the river would never rise past the staff. The staff took root, grew into a large tree, and the river never flooded past it again. He drove out the demons from idols and people ... and a great many more miracles.

On this feast of Saint Gregory the Wonderworker, Dom Guéranger writes: "Gregory was born in New Caesarea around 213. He was a disciple of Origen and became bishop of his hometown. For his doctrine and holiness, and also for the number and brilliance of the extraordinary miracles that he performed, he was called the 'Wonderworker.'"

At the time of his death, he asked how many infidels were left in his diocese of New Caesarea and was told there were only seventeen. Giving thanks, he said: This is the same number of believers in the beginning of my episcopate.

He wrote several works which, along with his miracles, illuminated the faithful of the Church of God. He also had the spirit of prophecy, and foretold the future. He died between 270 and 275.

As we can see, he was a great saint. Let us examine a little the nature of his miracles so that we might understand something of his mission. It is interesting to see that among the great variety of saints, Providence endows most saints with the power to work miracles. However, only some specific saints work many miracles.

There is a profound reason for this. The miracles wrought by the same person to a greater or lesser degree indicate the intensity of God’s extraordinary intervention. Because it is already unlikely for a person to work one miracle, but it is even more unlikely that he will work many. Of course, all miracles give more glory to God.

Here is a man who seems to have been chosen to show that the great gift of miracles of the Old Testament as well as that of the early Church, are still maintained in the third century in which he lived. What is interesting about his miracles is that none of them can be “explained” by experts as miracles caused by suggestion or illusion.

It is understandable that a madman might say that a cure at Lourdes is wrought by the power of suggestion. However, one cannot say the same thing about a huge boulder. No boulder moves through power of suggestion. No one can saw that a lake dried up of its own accord.

Someone might say: No! He simply deceived the people who saw those things.

However, illusions do not last a lifetime. A boulder that is here and suddenly moves over there cannot be the impression of the people who are watching. When the power of suggestion wears off, we must ask: Where is the boulder? Is it back in place? The lake was wet. When those who had the impression that it dried up lose that impression, will the lake be wet again. Yet that is not what happened. The lake was dry for good.

The instant growth of a tree in the riverbed from the staff thrust into the water was not just an illusion. After the illusion was gone, the people should have seen the stick again but they continued to see the tree.

They saw a tree growing to the point of changing the course of the river. These are categorical, undeniable miracles. The Church works miracles, and Providence has given Her the gift of miracles to show that the Church is divine. Was it only for this reason? No, it was not.

The reasons why this saint asked for those miracles show that Providence has other purposes in making miracles. Take for example the huge boulder that was moved to make way for the building of a church. We see that this huge miracle was done for something that was not extremely important in itself. Usually when a place is not suited for building, we build somewhere else. A boulder hindering the construction of a church is not a hopelessly insurmountable problem. Providence gave Saint Gregory the grace to work this miracle which was not an urgent matter to show how God is truly a father to us and how maternal Providence can be.

That is to say miracles do not happen only when we are in anguish, facing the greatest tragedies. God is our father and Our Lady is our mother. They give us huge graces with a magnificent liberality even when we are not in the highest affliction. These miracles show us how we need to ask even for things that are not very important. We must ask a lot, ask insistently. These requests will be granted.

The proof is this huge miracle worked just to simplify matters so that the building of a church would be easier. As for the other miracle, two brothers were fighting over a pond, so he dried it up. It is a miracle, a kind of mischievous punishment on these brothers. It is as if he was saying: you are tearing each other apart over the possession of this pond. I will dry it up so it belongs to no one. It was basically a little family squabble. He could probably have solved the problem by giving the brothers a good scolding. It is a little domestic quarrel that was not a great tragedy. However, he wrought a miracle to solve the problem.

The third miracle was to prevent the flooding of a river. Throughout history, rivers have flooded. Man would continue all the same, if the river continued to overflow.

What is the great lesson of these miracles? It is that if God heeds the request of a saint for these trifles, we also can be heeded when we ask for much more important things. He who can do much, can also do less. In this case, it is a more extraordinary miracle when and because it is worked over a trifle than when worked for something more important.

For the needs of our spiritual life, how many boulders need to be removed, how many ponds need to be dried, how many floods that overspill need to be remedied? How confidently we must therefore turn to Our Lady, asking her for these favors!

Someone might object: "Dr. Plinio, I wish it were as you say, but the point is that I am not Saint Gregory the Miracle Worker. He is a saint, and he could obtain it." I say: He is in heaven and today is his feast day. Let us ask him today, he will make an even greater miracle. Let us ask him for this grace: That when asking for heavenly things we may act with this holy freedom, I would almost say with this holy candor of asking for great miracles for our small things.

You cannot imagine how much one actually receives by acting in this way. This is the encouragement that the life of this saint should give us.

There is an insistence in the story of his life that he cast out demons. He did this in two kinds of places: idols and people. The idea that idols have demons that must be expelled is hardly an ecumenical idea, for if all religions are good, there are no demons in any idol.

However, I take this opportunity to say that the ancient Church Fathers said there were demons in idols, and many times there were. Thus we should be aware of the fact that it is very normal for demons to exist also in non-Catholic churches. When one passes in front of a non-Catholic church, a Protestant church, mosque or schismatic churches, we should remember this point. We should pray an ejaculation to our Guardian Angel. No one knows the danger that these dens of heresy pose. This practice is very good because it defends our soul against the devil, and instills a real sense of objectivity with regard to wrong churches and heresy. It is an attitude more necessary than ever.

In the end, the victory of this saint is non-ecumenical. When he asks how many heretics are there in New Caesarea, they answer seventeen. He manifests his joy: “When I began my bishop’s tenure the faithful were seventeen.” The situation had been turned completely around. It was his nunc dimittis. His work was done, it was consecrated, and he died giving his diocese to God.

The preceding text is taken from an informal lecture Professor Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira gave on November 17, 1965. It has been translated and adapted for publication without his revision. –Ed.

No comments:

Post a Comment